By Trey Brasher Beta-blockers are a class of drugs most commonly prescribed for reducing hypertension (lowering blood pressure) and widely considered one of the most important discoveries in medicinal chemistry in the 20th century (Stapleton, 1997). Beta-blocker’s mode of action is semi-selective antagonist affinity for the beta-adrenergic receptor system, a blockade that stops the action […]

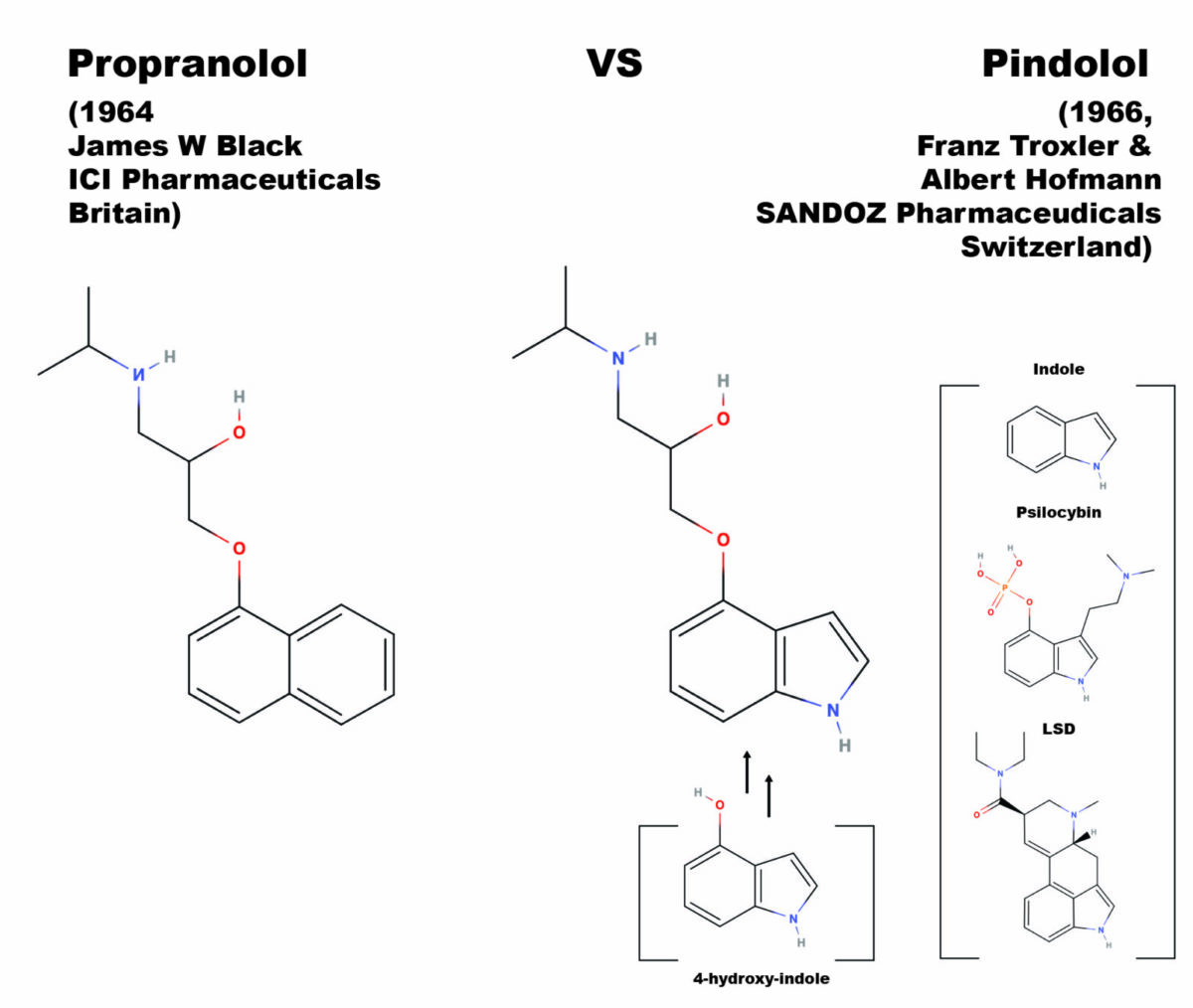

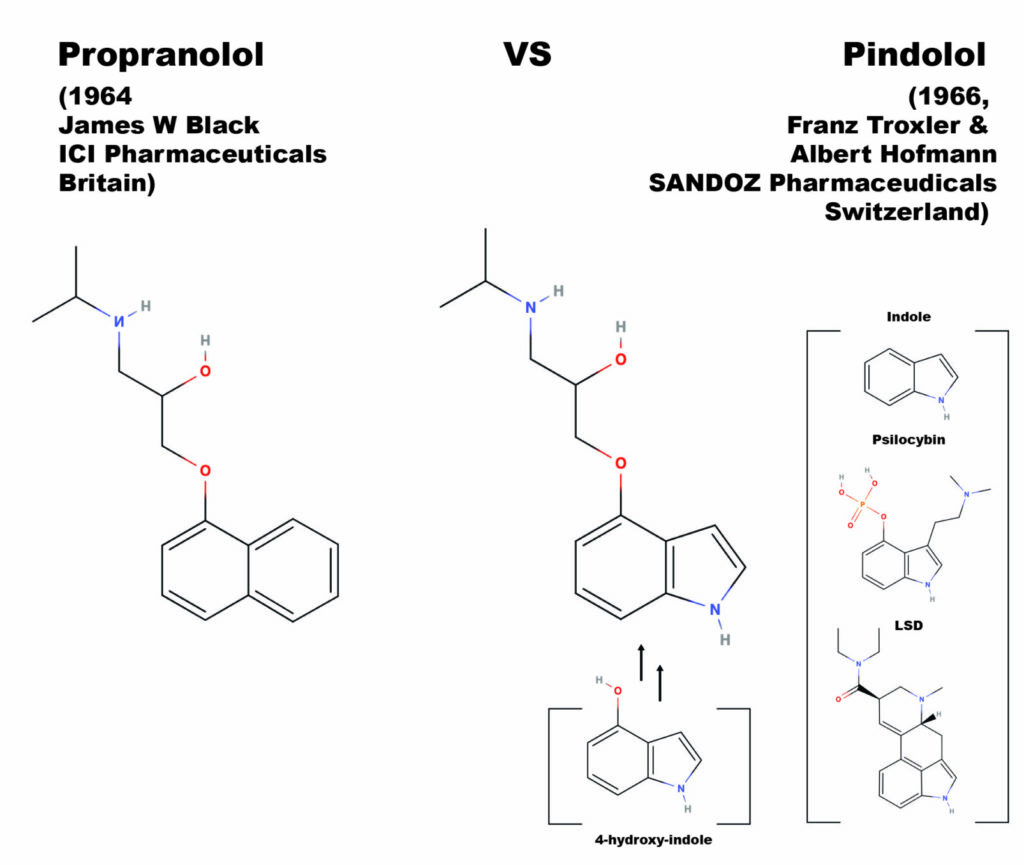

Beta-blockers are a class of drugs most commonly prescribed for reducing hypertension (lowering blood pressure) and widely considered one of the most important discoveries in medicinal chemistry in the 20th century (Stapleton, 1997). Beta-blocker’s mode of action is semi-selective antagonist affinity for the beta-adrenergic receptor system, a blockade that stops the action of the endogenous ligands, adrenaline and norepinephrine. The corresponding reduction of blood pressure makes beta-blockers a first line treatment for angina pectoris (a type of cardiac related chest pain), heart attack patients, and in the management of arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms). Chemically, most beta-blockers are ethers where the ether side-chain consists of a propanolamine with an isopropyl group on the amine nitrogen (in IUPAC nomenclature this is 2-propanol, 1-[isopropyl amino]-3-(1-R-Oxy)-salt, where the R is a ring system, and the salt is generally a hydrochloride). Other well-known beta-blockers are substituted at the alcohol oxygen.

The first clinically successful beta-blocker, propranolol, was developed by Sir James Black in 1962, at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) pharmaceutical division in England. In 1958, building upon the assumptions in Raymond Ahlquist’s theory that both an alpha and beta receptor for adrenaline controlled the cardiac system, James Black decided to search for a new type of drug that would reduce the demand for oxygen in cardiac systems where arterial diseases were reducing the oxygen supply. His first breakthrough on a beta-antagonizing chemical was pronethalol. The addition of an oxymethylene bridge (the ether linkage) to pronethalol gives the structure of propranolol, which pharmacological testing demonstrated to be superior to pronethalol in terms of toxicology, side effects, and potency. Thus, the first clinically significant beta-blocker was born and provided Black’s proof of concept for the cardio protective effect of beta-adrenal antagonism. The name propranolol comes from the propanol-amino-ether side-chain, which is the critical moiety (part of the molecule) for potency at blocking the beta-adrenergic receptor.

Spurred by the developments coming out of the lab of Sir Black, pindolol was developed in the lab of Albert Hofmann, by then famous for both the invention of LSD and the isolation from Psilocybe Mexicana of pure crystalline psilocybin, and then its confirmation by chemical synthesis. Seeing the British advances published in 1964 in the area of beta-adrenal antagonists, Albert Hofmann and his laboratory partner Franz Troxler, synthesized and tested a similar compound for SANDOZ, a major Swiss competitor of ICI. The idea for pindolol was to replace the naphthyl moiety in the propranolol molecule with another bicyclic system, the indole rings. The indole rings are the base of both psilocybin, psilocyin (which Hofmann also isolated and synthesized), LSD, and is the base of all tryptamine psychedelics, the number of which has hugely expanded since the isolation and total synthesis of psilocybin in 1957. The name pindolol reflects the swapped in indole moiety, being a portmanteau between propranolol and indole.

Black’s group utilized 1-hydroxy naphthalene as the starting material, using the hydroxyl oxygen as a nucleophile. Troxler and Hofmann figured the same reaction could be carried out with a hydroxy substituted indole ring system. It is thought that the original synthesis was carried out with a stockpile of 4-hydroxy indole left over in Hofmann’s lab from work on psilocybin, psilocyin, and other 4-hydroxy tryptamines; during around the same time Franz Troxler and Albert Hofmann had been using the 4-hydroxy indole to develop synthetic psychedelic analogues of psilocybin. Two of these, 4-hydroxy-n,n-diethyl-tryptamine (4-HO-DET) and its phosporyloxy analogue, Ethocybin (4-O-phosporyl n,n-diethyltryptamine), were later tested as active psychedelics. Troxler and Hofmann appeared to have used the same synthetic route as James Black’s team, treating the 4-hydroxy indole with 2-chloromethyl-oxirane in a kinetically controlled epoxide ring opening reaction. Step two is treatment of the resulting chlorinated propanol sidechain with isopropyl amine, substituting the chlorine for the final secondary amine substituent with an Sn2 direct substitution reaction. In some versions of this reaction, NaOH is included in the first step, reversing the order of the reaction steps by causing the Sn2 to occur first and an ether of methyloxirane to be formed.

SANDOZ patented Troxler and Hofmann’s discovery in 1969 and the drug arrived on the US markets in 1977, even as psilocybin itself (under the patented trade name Indocybin) was withdrawn from the market by SANDOZ after an international backlash against another of its psychedelic products, LSD. It remains unclear to what degree the 1966 decision by SANDOZ to cease production of LSD and psilocybin contributed to the wider pharmacological exploration of indole derivatives in Hofmann’s lab, and ultimately to the development of non-psychedelic indole derivatives such as pindolol.

In 1988 Sir James Black was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for the discovery of propranolol and the creation of the beta-blocker as a new class of drugs. His crown jewel propranolol continues to yield new medical value even into the 21st century. Propranolol is now commonly prescribed as an anti-anxiety drug and is currently under investigation in clinical trials for the treatment of PTSD. While both pindolol and propranolol are still used to this day, the history of pindolol is far less known, and its connection to psilocybin lesser known still.

At Unlimited Sciences, we dig deep to bring you the bizarre and beautiful. Our combination of research and storytelling ensures a balanced approach to the psychedelic space. We aim to educate those to make informed decisions about dose, safety, and substance, and continue moving the psychedelic science forward into the future. If you value the freedom to explore your own body and mind and information that allows you to do so safely, we invite you to consider a donation to Unlimited Sciences!

No comment yet.

Join our email list and get immediate access to part one of our psilocybin guide. You’ll also get the latest in how we’re bridging the gap between science and soul: psychedelic research updates, real-world findings, community-driven education, personal stories and expert insights on natural medicine.

Advancing Real-World Psychedelic Research and Science-Backed Education

Unlimited Sciences is provided with a nonprofit status by fiscal sponsorship through Realm of Caring Foundation.

Federal EIN: 46-3371348.

© 2025 Unlimited Sciences. All Rights Reserved.

Designed by Gloss